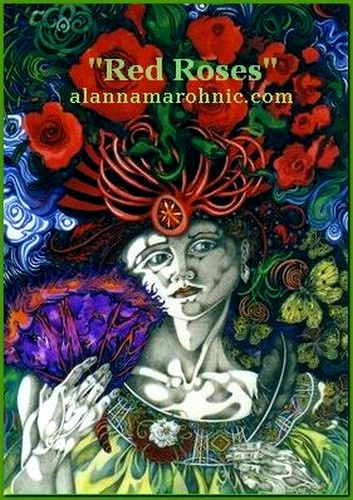

Terrible Beauty |

Alanna Marohnic's work allows us a rare We are immediately struck by the luminous nature |

|

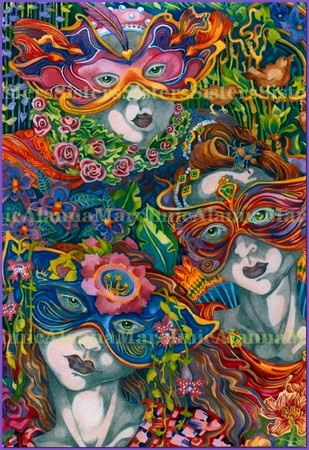

In her Dream Wave vision, a child's dreamscape is |

mind of an artist must be swept aside. A more |

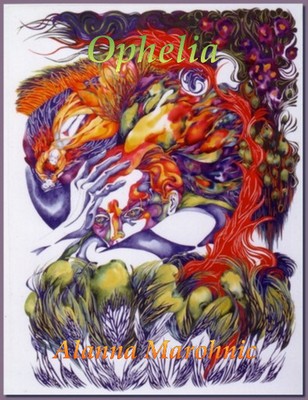

At the start of her creative process, Alanna is often |

As experience increases, Alanna finds her emotions Even through typically optimistic colouring it's a desperate Eroticism owns a thread in the web of Alanna's work as |

|

|

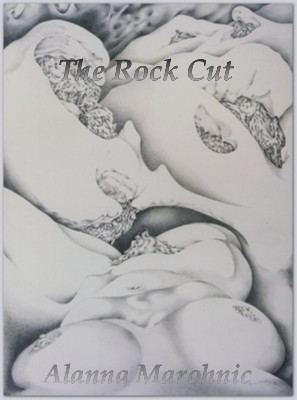

Throughout art history most female nudity is painted by The fragility of life in Late Summer is the prevailing artistic Ultimately, a walk down Alanna's garden path offers an

|

Alanna works from real life or memories. Her studio is full Where Alanna's mind, spirit, hand, and brush meet paper Scot Kyle |

|